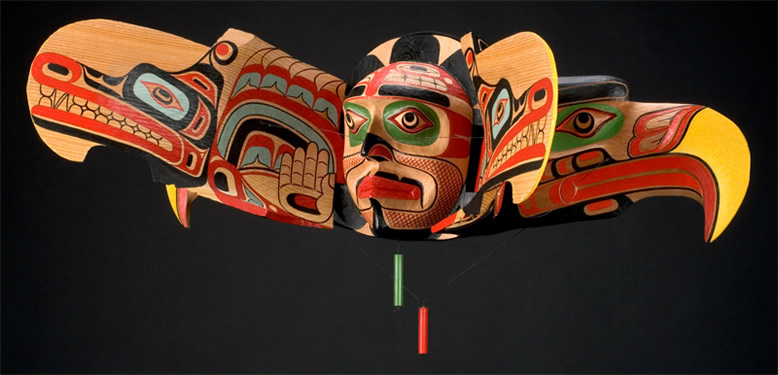

Eagle transforming into Sisuitl mask (by Richard Hunt)

‘[You humans] are not as free as you think you are; your cleverness and pride bind you to the truth. Don’t you see what you are doing to us and yourselves?’ ~’The Animal’s Lawsuit Against Humanity’, 10th Century Iraqi Fable.

Over the course of the past year I have discovered and immersed myself in a relatively new philosophical school called variously ‘Speculative Materialism’, ‘Speculative Realism’, and ‘Object-Oriented Philosophy.’ While not an overtly political form of philosophy, being much more in the realm of metaphysics and the like, it nonetheless has political implications, as all schools of thoughts do when you look hard enough whether they mean to or not. Since international relations theory is a part of what is covered on this blog, I would like to make a brief case for how Speculative Materialism could impact the study of that subject in the future.

I will confess that I am somewhat new to this school of thought and have not yet read all of the works I mean to someday. I have, however, read the text that probably started it all: Quentin Meillasoux’s ‘After Finitude’ as well as Steven Shaviro’s ‘The Universe of Things’ and the essay collection by multiple authors of ‘The Non-Human Turn.’ This is not a field of my expertise by any means and I have more reading to do, with ‘The Fragility of Things’ at the top of the list. So as of yet I cannot speak with the confidence I could on say historical or geopolitical manners. That aside, having delved into this field on the side in the past year has me with a few observations.

First, what is speculative materialism? To put it in the simplest terms it is the simultaneous rejection of platonic idealism and postmodernism relativism. It should be obvious to regular readers of this blog that I already do both (and indeed, have for most of my adult life), but this is a framework for viewing material issues (as material issues are what matters) in a way that divorces them from simply being objects under human observation and interaction to independent (but non-idealized) objects in their own right. Rather than embrace Platonic desires of therefore setting these objects up as pristine and independent, speculative materialism focuses as much on the interrelations between said objects as just as important a part of their existence as themselves. But the key here is to de-anthropocentrize the relationship factor. A rock with a stream or a fox in the stream standing on the rock all create relationships in real physical space that have nothing to do with ideals or even feelings about them, and thus the relevance of human consciousnesses as a central force is called into question, or at least its uniqueness is. In a materialist world view (i.e. the only world view that is not entirely based on faith) the consciousness is affected by the objects if at all, but not so much vice-versa. Being trapped between the utopian idealism of the left or the golden age worshiping revanchism of the right has no place in this view, and the fatuousness of consciousness-worshiping postmodern identity politics has even less. What has long been a period of affluence based ideology for middle class people to feel educated and make a pretense at being impartial observers has been dated for a long time, but postmodernists still thought themselves as fashionable and forward thinking. They never were, but now there is a new kid on the block as a philosophical school to finally show the sportscar driving midlife crisis having ageing group of people that no, they are no longer even young nor particular culturally relevant…so maybe its time they stop hovering outside of college campuses trying to pick up prospects. If I may quote once again from ‘The Animal’s Lawsuit Against Humanity’: ‘If this is how you humans glorify yourselves , then your ignorance speaks against you. And as for what you have argued-why, it is vanity, hot air, lies and fabrications!’

That is a very stripped down version of speculative materialism, but it will do for now. What I want to mention is how much ammunition this gives the anti-idealists among us to recognize the coming crisis of world affairs is going to be in large part ecological and thus the political affairs that will arise from such ecological issues will be decidedly material. It also helps explain in more philosophical terms the issues I have with economic globalization. While no one would deny it brings benefits, I view it as an experiment running long past its usefulness as state actors are still the most powerful actors on the world stage and must make laws and policies to reflect the differences of where they are in space and time. Therefore, global economic projects (unless they become about ensuring the installation of more sustainable energy sources or joint national parks) more often impede the policies needed to be enacted by societies. Much necessary divisions of strategies to tackle issues (Florida and Iceland will experience global warming very differently, after all) reflect that the relationships we have with the material world are not equal but based in the physical and political geography of where we spend most of our time. This in turn dovetails into geopolitics which recognizes that the use of space is the key determining factor in diplomacy, conflict, and alliance building–and sometimes even capacity for development.

The relationships we have with the non-human world around us matters as much as that with the human. But this is not some absolutist hippie creed, anything but. We are a predatory species, and like other predatory species we do what we must to survive. But in this ruthless and inevitable struggle we can at least acknowledge the context of us as reactors as much (if not more so) than actors. Much as we view the rest of nature. And this will not be some simple exercise in hubris reduction, but a way to mold our political and social strategies to give the best return for less effort. Something about it all makes me suspect speculative materialism might just be a good corollary for defense realism as a foreign policy theory. Our species base material needs are the real driving both of domestic and international affairs, and attempts to pretend otherwise often lead to error if not outright ruin.

Since the trickster is the theme of this blog it might perhaps be best to sum up my feelings with a quote from Dan Flores’ excellent book study of the coyote ‘Coyote Nation’ which shows why I find the myths of polytheism so much more enlightening to how the world really is than that of monotheism. After all it is under aninism and shamanism that the inter-contentedness of humanity as part of the animal world is constantly reinforced:

‘But what, no moral code in these stories? No promise of eternal life, no salvation from death? Coyote stories offer up none of these things…It ought to be said that Coyote stories are not really for visionary dreamers who expect to change the world. Coyotism is a philosophy for the realists among us, those who can do a Cormac McCarthy-like appraisal of human motives but find a kind of chagrined humor in the act, who think of the human story as cyclical…Coyotism tells us that while we may long have misunderstood the motives of our behavior, we’ve also known how human nature expresses itself. And who better to illustrate that than self-centered, gluttonous, carnal Coyote?’