I was originally going to write this post anyway before all the Gaza Strip stuff happened. I was simply waiting to get back from an international trip before doing so. That a new round of fighting between Israel and Palestine broke at the tail end of my trip only added from my desire to write such a thing. And while I know it would get more attention if I published it externally at some official publication, I feel few would allow me to say what I really want on the subject.

Every tribal war or local territorial dispute now has taken on global dimensions due to media saturation, the universalist claims of the American state, and the existential rhetoric its opponents adopt in response. This leads to a massive distortion in what people regard as self-interest, rejecting rationalist prudence for a crusader mentality of whatever the pet cause of the day is or ones personal/psychological vendettas.

People who live in North America for instance, but have no friends or family in either Israel or Palestine, are deeply invested in a tribal ethnic war that has no bearing on their life. Or, would have no bearing on their life were it not for the risk of outside power escalation. And the primary driver of outside power escalation is of course countries (and their publics) wanting to ‘do something‘. This is why interventionist states and their mouthpieces in the press are so obsessed with human rights narratives. They are always seeking to manufacture consent for the next intervention. It is increasingly obvious that in order to care about peace and stability one must not embrace, but renounce, the human rights focused view of the world.

While I am sure a large amount of the religious fanfiction of some cultures draws them like flies to shit when conflict in the Levant breaks out, this region is hardly alone in attracting this kind of attention. Having a national interest based discussion about Ukraine in North America, for instance, is always buried under layers of posturing bullshit about democracy, clashes of civilizations, and whatnot.

The obsession with tallying ‘War Crimes’ is a big part of this and may be central to this kind of rhetoric. The problem is war crimes trials are always by necessity victors justice, and without trials the concept has no meaning but a kind of whine. Power differentials make the concept situational as we know certain people will be punished and others not. Furthermore, such discussions feed into a false belief that war can be tamed and functions as a kind of courtly jousting match on a predetermined field. But in an era of mass urbanization, high explosives, and existentially justified stakes, this is impossible. Any war is a war on civilians and therefore the point of ‘war crimes’ is moot. To support a military operation is, inevitably, to support war on a society, not just its front line military. Considering the logistical network required for militaries to function this is both logical an inevitable. But it also means that to support a war means, undeniably, support for war on civilians and all that entails. This is why I personally support only a very few military operations even though I am not a pacifist. In my adult life I have only directly supported counter-ISIS and counter-Al Qaeda operations. And yes, this means I was fully supporting the demolition of places like Aleppo and Raqqa. Nor did I have the gall to pretend the policies I was advocating were actually for the good of the people being bombed, because no such policy can be good for everyone. The very existence of foreign policy presupposes the obvious observation that there are multiple groups of people with divergent interests.

The political center and its lapdog journalists, in love with war as they are, are actually made more hawkish by their faith that war is a controllable, even chivalric force of social change. Their maudlin humanism is not a hypocrisy except in rhetoric, it is a natural extension of their world view of treating war as transformational and moral rather than the breakdown of order and the failure of diplomacy. But some, even going back to Sunzi, warned us of the truth from the start: War is always a failure and a dangerous roll of the dice, even when it is necessary. That is why it must be kept to a minimum even though it is always prepared for as inevitable. But when it is embraced, it is only rational to embrace it to the maximum. If you believe a war is necessary, you believe the attempted demolition of another society is necessary. At least have the honesty to admit it. All people have a place where they reach this point. It is dishonest to deny it. And becoming squeamish when your faction does not behave in the way a suburban commentariat wishes just shows your views are superficial at best, calculated for social prestige at worst.

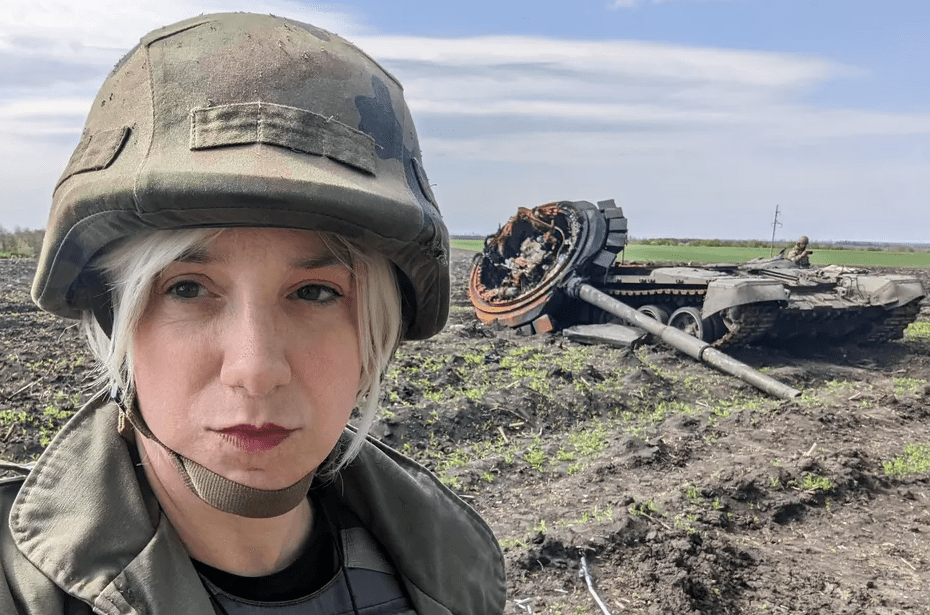

But let us not just pick on the centrists. The past month has shown us the worst spread of leftoid and rightoid thought across the board. Our entire culture is unprepared to seriously engage with nuance and restraint. Earlier, a moronic English language spokesperson for the Ukrainian military threatened U.S. citizens for criticizing involvement in the war. Even a cursory examination of this person’s past reveals a sadly predictable pattern: the lost soul in search of a cause who wanders the world looking for a fight that isn’t theirs. Having finally found one (a war which, since the failure of the first Russian offensives anyway, is basically now one of local territorial control) the foreign volunteers have adopted as a cause above and beyond their empty listless life in an attempt to find meaning they are too weak to make for themselves. A lack of self-cultivation leads to radicalization abroad.

I used to analyze patterns of extremist recruitment for jihadist networks when I worked for the U.S. government. It is interesting how many of the psychological identifiers are in place for western Ukraine volunteers. Downward mobility, an obsession with culture war and global teleology, the desire to erase one’s own personal insignificance by joining an existential cause beyond themselves. When these people come home, mark my words, they will destabilize their home countries. They are the new Freikorps, or Japanese army officers after the Siberian Intervention, or jihadists. Their jihad is Reddit (or Azov) and their connections and sense of entitlement make them a domestic danger. At the very least they should be put under surveillance. And for me, a general opponent of the surveillance state, to say that means I am very serious about the danger these people pose to the rest of us.

The right, if anything, has beclowned itself even more than the left and center. At least Ukraine ties into great power competition and therefore is a national security issue of some kind. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict can’t even do that unless you think Saudi Arabia and Iran are global powers…an odd thesis. For years I have been warning the realism and restraint community (who has been rightly happy with more republicans listening to its argument than at any time in generations) that this was a fair-weather situation. I told many people, again and again, that the second something happened to Israel you would see the Bush/Cheney marriage of evangelical end times prophecies and neoconservatism come roaring back to the surface like it had never left. That happened this week. All the Big Tough Guys who pose about being better than the pussy humanists now shriek about seeing the face of war brought to their darling little pet nation, Israel, the nation they have sworn allegiance to above that of their own. This transferred nationalism allowing them to go to places the regular old kind at home is inadequate for. The conservative love of a country which could be considered the biggest ‘welfare queen’ in American history, one that bombed the USS Liberty and constantly schemes to involve Washington in more Middle Eastern quagmires, is a masochistic and yes, quite cucked, affair. Any utility this alliance once had ended with the end of the Cold War, and it now serves only as a burden. Yet these sentimental rightoids cannot stop themselves. Its the Bible Country and its under attack! Tom Clancy would want us to be the heroic protagonists of this new Battle for Civilization! The Left Behind series is now real- get ready to RAPTURE!

And these American Pied Noirs are just waiting to see their Biblical fever dreams reenacted at home as well as abroad. Once again, surveillance is needed. In a rational state without delusions of Imperial Globalism, that’s what we would do. We would treat people more interested in fighting other people’s battles as inherently dangerous and unstable, and merely waiting to bide their time to import those battles back home. The historical record on these type of people is very clear on this point. At the very least their antics should be tracked and publicly documented on public forums.

Conflict zone interest should be categorized on a location-based capacity. The further something is located from you, the less relevant it is. Its ability to impact you only worsens the more things get involved. Anglos are taught from birth to see all struggles as global and good vs evil, but they are inevitably local, contextual, and tribal. They can be everything and existential if you live in or near a place, but are not if further afield. The true danger of globalization is that every struggle can become globalized.

Conflict is both inevitable and eternal. Understanding this, the only rational conclusion is containment, not intervention. Containment is not pacifism and requires both vigilance and force, but it can and will reduce the spread of outbreaks of violence. Those who wish to make local conflicts go global are complicit in making the world a more awful place, be they hawkish politicians or these psychological damaged war tourists. Diplomatic wisdom is being rooted more in place, in a very real physical sense, than being rooted in some Platonic-Manichean realm of battling ideals. It is spatial relationships that should concern the makers of foreign policy, not dreams of world transformation.