One of the most precious local resources you can have is a used bookstore. Especially one with a focus on things usually not held at other similar establishments. Even in the age of widespread Kindle access (which as a person who frequently relocates and likes to travel light is usually a good thing), e-books tend to come to people either by algorithmic recommendation or from specific search. But sometimes, what you need to complete the collection is something you don’t even know exists. Or that is too obscure to be well known enough to get an electronic adaptation.

So was it with me this month. I knew I had to write something on the utility and necessity of divergent governance, world views, and culture complexes. Specifically because there seems to be a kind of partial resurgence of Fukuyama-Friedmanism among a surly establishment. But I held off due to lacking a specific frame of reference worth writing about. And then there was the missing link right on the shelf in front of me in the used book store. A book I had never even heard of previously; Maruyama Masao’s ‘Studies in the Intellectual History of Tokugawa Japan.’

The uniqueness in shaking up a complacent world plagued by used bookstores overlaps with the themes of appreciating the uniqueness of divergent societies. It is interesting to think how the big panic among bibliophiles in the 90s and 00s was how giant bookstore chains were going to eat up all independent booksellers. There was even a terrible romantic comedy about it. But now we see that smaller bookshops are doing comparatively well to these former behemoths, specifically because of their uniqueness, while the neoliberal edifice of the giant chain is the one which struggles to survive in the internet age.

Ask any farmer, herder, or long term trend examiner if they think monoculture is a good idea and they will tell you it is not. The Irish Potato Famine, the Dust Bowl, the modern day Khat farming in certain parts of the world, and many more examples show this to be the most dangerous thing humanity can do on the macro-scale. The same principle applies to politics and economics, albeit in a less immediately quantifiable way. Too much of one thing, no matter how apparently successful it may appear to be, invites disaster the second this singular thing goes wrong. The degree of interconnected commerce the world was under at the turn of this century was viewed by most in the developed world as a good thing, but the worldwide collapse caused by the failure of the American housing bubble caused the Great Recession of 2008 and a series of violent economic disruptions we are still living under today. Present conditions of social homogenization in the internet era are similar in that an apparent triumph by present teleologists is not but hubris before an inevitable collapse. Those prepared to diverge and capable of learning from different examples will weather the storm better than those who simply follow trends. Not because they simply adopt a contrarian world view (reflexive contrarianism is simply a values inverted take on still being enslaved to present trends, after all), but because they show that alternatives are not just possible, but necessary. Such examples do not exist to be copied, since they are context dependent, but because they can be proportionally learned from in a way that cultivates critical thought and distance from mandatory trend chasing. This is why diversity, which, sorry DEI HR people, includes ideological diversity, is a critical value for the flourishing of the human experience. And it is especially critical for the scholar of the humanities-itself a discipline subjected to a forced conversion of sorts in the last decade.

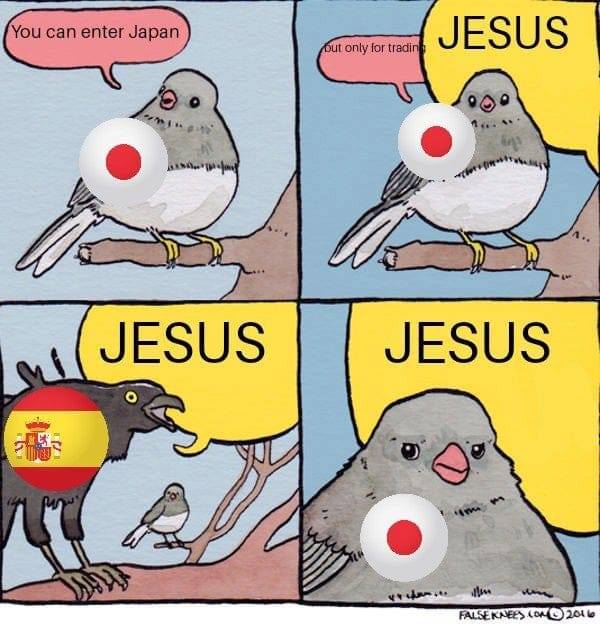

The Tokougawa Shogunate was in many ways a conscious effort to diverge from what seemed like omnipresent trends then affecting Japan. Coming to power after generations of constant regional warfare, it was a thoroughly feudal but also self-consciously centralizing force of stability. The ruling elites had spent a thousand years being Sino-Weebs and nursing an inferiority complex towards China and blindly copying its philosophical and political debates. Meanwhile, in the south, enormous amounts of people under the influence of Portuguese and Spanish missionaries were converting to Christianity, a religion of mandatory monoculture with an expressly ‘globalist’ intent to culturally assimilate the planet into a teleological quest of seeing the human experience of a universal battle of good versus evil.

Though this was too early on in the period of European ascendance to be like the threat that would have to be adapted to in the 19th Century, Spain had recently conquered the Philippines and the ability to project its fleet in the Pacific was a real and immediate threat.

Japan had always been a place of syncretic tolerance when it came to religion. Buddhism and Confucianism could exist in syncretism or modus vivendi with local Shintoism and so they could be tolerated. Christianity could not play well with others, and thus it was not tolerated. It was, in fact, thoroughly exterminated. A decision which might have saved Japan politically and certainly saved it culturally. A side effect of this was the closing of the country to all but regulated amounts of Chinese, Korean, and Dutch commerce.

The conventional narrative at this point is that the Tokugawa Shogunate sat in a state of pure stagnation for over 250 years. Peaceful, yes, but undynamic. This is not true. Or, more accurately, it was not true until the last half century of its existence. For while there were many onerous, unnecessary, and even farcical rules of the closed country such as related to travel and adoption of technology, overall this was a remarkably successful and dynamic government. Edo went from a tiny fishing village to one of the largest (and one of the cleanest, somehow) cities in the world. Peace became the norm for centuries. The population exploded initially and the government responded by instituting the first country-wide forest preservation program in history. The creative world took off, especially in arts like wood block printing. The country would eventually fall behind, as all orders do under the entropy of time, but not after a massive and impressive recovery from what came before.

This brings me to the book I just finished, ‘Studies in the Intellectual History of Tokugawa Japan.’ The above was something I already was quite familiar with, being a lifelong student of East Asian history. What I did *not* know, however, was the specific intellectual currents of high Tokugawa thought. And Maruyama’s book (first written in the 50s and reissued and updated in the 70s) filled this void. And within the story of this period of philosophy are many useful ideas for those concerned with resistance to monoculture and who value practical steps for how to develop alternatives.

At first, the Shogunate decided to get into Confucianism hard. Neo-Confucianism, specifically. This was because it filled a very specific niche in converting the potentially dangerous samurai class into good administrators and bureaucrats. This process was so successful that it was basically completed in less than two generations. Once that was the case, many intellectuals began to realize that Confucianism may not in fact be an ideal synthesis for the Japanese context. Neo-Confucianism, the then dominant strain, in particular was extremely moralistic and idealistic, demanding a kind of cultural uniformity from ruling to ruled based out of the Song Dynasty priorities it has first arisen from. Specifically the thought of Chu Hsi, who was a kind of Song Aaron Sorkin who held out that public policy would follow naturally from personal example and the ruling class’ commitment to principle above all else. A walk-and-talk of style with no substance but that of being desirable to emulate. Yamaga Soko, writing in the latter 17th Century, was himself a Confucian but found this Song world view alien and idealistic. He noted that the Song had preached these principles as they were humiliated by the Khitan and Jurchen and then wiped out by the Mongols in turn, so what actual use had this world view served? Song history was not more glorious than other Chinese Dynasties and its failure to secure its own stability made its moralistic traditions seem like compensatory coping. Surely, Japan needed something more grounded and less idealistic. Confucianism, according to Yamaga Soko, had to be recaptured from these Song revisionists and adjusted to be practical.

This began a growing rebellion against moral-idealism more generally and with greater degrees. Ogyu Sorai, also a Confucian, would end up unintentionally laying the groundwork for a full blown intellectual anti-Confucian reaction with his critique of being wedded to Chinese examples and practices when the reality that the Shogunate governed Japan, which had a different historical experience, beckoned. The core of this problem, according to him, was the commitment to universal principles that Neo-Confucianism espoused:

“All things in Heaven and Earth derive their forms from yin and yang and the five elements. They all originate from one and the same source. But once they have been transformed into Heaven and Earth and a myriad of things, they cannot be discussed in terms of principle alone. It is a great mistake to teach that human nature and Heaven are the same as principle.”

Sorai’s main focus was that history debunked rigid moralism. The more one looked at home and abroad, the more complex the story became, and thus the less relevant seeing the world through a single ideological prism became. Now that Japan had some stability and distance from the conflicts of the past (and raging abroad) it could reflect more on its own place, which was distinct but not exceptional. In another quote which sounds all too real today he says:

“The fact that even many men of good character become bad after the pursuit of learning is entirely due to the harmful effects of Chu Hsi rationalism. According to the Tung-chien kang-mu, there has never been a satisfactory person, past or present. Anyone who views the people of today with this kind of attitude becomes naturally becomes a man of bad character…Those who subscribe to the Sung scholars’ version of Confucianism insist on making a rigid distinction between right and wrong, good and evil. They like to have every aspect of all things thoroughly clarified, and in the end they become very proud and lose their tempers very easily.”

This was coupled with an awareness that not everything is interconnected. Creative pursuits need not reflect governing ideals or vice versa. The multiplicity of living was to be found in the division of human output into different fields, rather than trying to force them all together.

Coming later came thinkers like Motoori Norinaga, the real hero of this story, so far as I am concerned. For him, Sorai had not gone far enough. Human nature was part of the rest of nature, and thus beyond such quaint concepts of good and evil- as was the world itself. Confucianism had blinded people from simply adapting to their circumstances without a need for elaborate justifications. So too had Japan erred in trying to become Chinese when it was not part of China. It was the historical evolution of society that mattered in how it should behave, not some abstract non-historical ideal. The Shogunate, according to Motoori, was a highly successful government because it had allowed Japan to become something other than a Chinese pick-me or a Spanish colony despite being initially outclassed by both. Devoid of the imperial ambitions that would afflict later Japanese history, he spoke of a uniqueness without resorting to that other kind of moralism, chauvinism. Neither was he a nostalgic, despite his scorn for both Confucianism and Buddhism, stating:

“When I propound The Way I do not advise the people of today to behave like the ancients, unlike the Confucians and Buddhists. Any attempt to compel people to practice the ancient way of the gods in opposition to existing circumstances is contrary to the behavior of the gods. It is an attempt to outdo the gods.”

Within this thought, and that of its successors, came a litany of scholars who had unknowingly prepared the way for the dissolution of the very feudal order they were supposedly defending, with a general questioning even of the class system being teased just in time for the sudden crash into modernity that Japan would experience in the latter 19th Century.

Masao Maruyama’s book, needless to say, was a great find. And it cannot be ignored that the only reason I found this useful book on societal divergence and bucking moralistic trends in another time and place was because of a used bookstore that itself stood against the tide of monoculture in my own society.

To wish for a universal order in economics is to wish for monopoly. In politics it is to wish for monoculture. When monoculture fails it can drag everyone else down with it, so alternatives need to exist, even if only on the outskirts. Motoori Norinaga advocated for obeying the laws but understanding that the laws were temporary and people must always keep an open mind to governance. This becomes impossible if everyone, everywhere, is governed the same way. The more different people are, the easier it is to learn from them. When ensconced inside one moralist order, be it that of the Sorkinite libs, neoreactionaries, or the Neo-Confucian fanboys of Chu Hsi, we must treasure the opportunity to learn from divergence, both failures and successes, whenever possible. It is not thinking through received wisdom with no counter-examples that serves as our antibodies from the failures of the monoculture.

This is also why the ‘Tokugawa Option’ is superior to Rod Dreher’s ‘Benedict Option’ and other related examples of North American paleocon thought. They wish to wed their attempt at an alterative to the very first ideal of universalized moralism: Abrahamic monotheism. Missionary monotheism is the ultimate monoculture after all. It knows no limit on souls to harvest or geography to conquer. World views that seek to squash context and distinction for mass moralism behind a universal purpose are contrary to the necessity of upholding intellectual diversity. To opt out from the relentless groupthink cannot be done with a world view that sees all of Earth as its rightful dominion and sanctimony as its unifying principle. Neoliberalism, and especially its current evangelical incarnation of woke-progressivism, is nothing if not the direct intellectual descendant of Christianity. But the Benedict Option people are correct that alternative communities (plural, I would add) are needed. But to live in a modus vivendi with each other they must take divergence as the norm rather than unity. Communities that reject atomized liberal individualism can and should exist, but only as situational groups in time and space. This requires the rejection of universal moralism and the acceptance of a polydirectional world view. In theological terms the word is polytheism.

The Tokugawa Shogunate died when it became too old and obsolete. All things do. Furthermore, one should never seek to copy the past. But when it comes to thinking, in a future oriented way, of alternatives, divergent examples are more useful. The Shogunate is just one of these case studies. I have endeavored to mention others before on here and will continue to do so. But for now the most realistic way to get to the end goal of The Black Longhouse is by contemplating The Tokugawa Option and other such self-conscious societal outliers. We look at those who intentionally turned away from massive pressure to take another’s path in order gird ourselves for potential futures. How can we emulate their successes and avoid their failures to outlast the monocultural fads that seek to brainwash us into acquiescence?